Hockney – Film

David Hockney is considered to be one of the most significant artists of our generation. He’s been creating art since the 1960’s and, believe it or not, he is still at it today. His life is explored in the new documentary Hockney, to be released on November 28th.

David Hockney is considered to be one of the most significant artists of our generation. He’s been creating art since the 1960’s and, believe it or not, he is still at it today. His life is explored in the new documentary Hockney, to be released on November 28th.

Hockney was born in Bradford, UK in 1937. He graduated from the Bradford School of Art in 1957 and then studied at the Royal College of Art from 1959 – 1962. He was instrumental in the founding of the British Pop Are movement. In the documentary, Hockney gives complete access of his life – his personal archive of photographs, paintings, and films – with family members and close personal friends speaking about him as well.

Hockney’s art is very visual, very abstract, and he has been able to transcend the changes in the art world for over half a century. He’s been a success, but throughout his life he has struggled with his art, relationships, and the tragedy of AIDS.

Hockney was brought up in the time of austerity, and his first memories are of him hiding under the stairs during the WWII air raids. When he was young, his father told him ‘not to worry too much what the neighbors think’ and this might’ve set the tone for his art. He also loved going to the cinema – Hockney mentions in the documentary that painting and cinema have a much closer relationship than people realise. Hockney’s first time out of the UK was when he set off to New York City – where he had $350 to last him for two months. We are shown quite a few scenes of modern New York City which seem irrelevant to the era in which Hockney arrived. In 1964 he moved to Los Angeles and it was his time there where he produced his most memorable art – images of swimming pools and the people in them. His art was also very blatantly gay as Hockney was not shy about painting art that basically reflected his life.

But Hockey the documentary doesn’t show us his life story in chronological order. It goes back and forth between showing home videos of him with friends, present day Hockney musing on his life, friends from the yesteryear reminiscing about pivotal events in Hockney’s life, his sister Margaret discussing the time when they were children, and near the end of the documentary there is a three minute tribute to his mother, who passed away in 1999 at the age of 99. So Hockney in that sense is a bit confusing because it doesn’t follow any order, it’s just a series of talking heads (including Hockney’s) interspersed with his work.

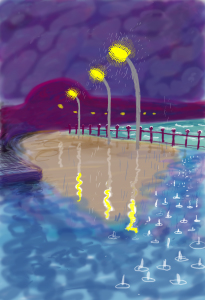

It is the art shown in the film that is breathtaking. Hockney created two very different landscapes for his work – the vast bright colorful spaces of California and the dark, moody hills of East Yorkshire. His work would start with a photograph, and from then he would reproduce it as a print, including friends and acquaintances in some of his paintings – some of whom discuss their memories posing for Hockney.

Some of his work shown in the film includes his ‘We Two Boys Together Clinging,’ an oil on board painting showing two men clinging to each other. ‘Pacific Mutual Life’ is another one of his earlier works and it is just that – a painting of the Pacific Mutual Life Building in Los Angeles. One of his most famous works is “A Bigger Splash,’ simply an unseen diver already in the water, the remnants of his splash backdropped by the beautiful house with palm trees and terribly blue skies. Every one of Hockney’s painting tells a story from his life.

‘Peter Getting out of the Pool’ also stuck with this same motif – showing Hockney’s then boyfriend Peter Schlesinger literally getting out of the pool, naked, with the ripples of the water drawn by Hockey to look like squiggly lines. When the themes weren’t about pools or homosexuality, Hockney liked to paint people. ‘Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy’ (1970) shows two friends posing in their living room. Hockney for some strange reason could not paint Mr. Percey’s feet so he had him burrow them in the deep shag carpet.

But David Hockney comes off as lonely. He has had bouts of depression during his lifetime, especially after the death of his best friend Henry Geldzahler – who passed away in 1994 of cancer. They were soul mates, travelling together, working together, and practically living together. Henry, who worked in the art world as a curator, is shown in bed with Hockney, cuddling, and also shown at a beach house where he and Hockney would escape to be creative. Also AIDS entered into Hockney’s like, and his friends say that it shook him to it’s core. Hockney, who is free of the virus, says in the documentary that he lost two-thirds of his friends to the disease.

But Hockney always reinvents himself. His interest in films and photography grew into almost an obsession. He was one of the first artists to optically produce images, creating paintings that begun as a series of photographs taken from different angles of a single subject into one single piece of work – it’s a technique no else had ever done so successfully before. And Hockney has had a very successful life and career as an artist. And it’s hard to believe that at age 77 he is still working in the studio seven days a week.

Director Randall Wright was very fortunate in two respects in the making of this documentary; that Hockney was still alive, and that he fully cooperated with him for this documentary. Hockney gave Wright free reign to do whatever he wanted with his personal archives – the first time Hockney has ever done so. Hockney even gave Wright permission to use the many unseen experiments with film and video and his early still photographs. This is not the first time that Wright has worked with Hockney. In 2003 he directed ‘David Hockney: Secret Knowledge,’ which explored Hockney’s theory that artists have been using optical devices since the 15th century. But in Hockney, it’s all about the man, and the myth. But perhaps Wright is too close to his subject and has known him for a long time because after watching Hockney I still felt that I didn’t really understand him and felt like I had just been given a video tour of his art – abstract to a point of not knowing what to make of it. And at the end of the documentary, we see Hockney aimlessly walking around his house, not giving much of a dramatic ending to this film.